|

|

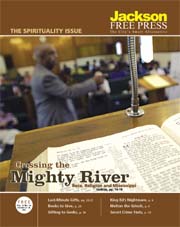

Crossing The Mighty River: Race, Religion and Mississippi

December 21, 2005 Cover Story in Jackson Free Press

see original story at: http://www.jacksonfreepress.com/comments.php?id=8088_0_9_0_C

by Sophia Halkias

Photo by William Patrick Butler

At the climax of the 11 o’ clock church service at Galloway Methodist

church, the Rev. Ross Olivier assumes the pulpit to deliver his sermon.

Olivier’s polished demeanor gives no air of being weathered by years

of struggle against apartheid in South Africa. He does not let any possible

scars from that experience stop him from addressing the hard issues before

American Christians. His sermon, which is riddled with messages of the

social Gospel, is an open call to Christians to unseat themselves from

complacency and work toward living out the mission of Jesus Christ by

working for justice.

“People, black and white, why don’t you stop killing each other

and have a new beginning?” Olivier asks at one point. “It can

be true for you, for all of us.”

Seated to Olivier’s left is Harlan Zackery, an African American who

serves as the church’s music minister. Seated to his right is Michelle

Foster, a white woman and pastor. This scene is a symbol of religious

progress in the Deep South. It is fitting that it unfolds at Galloway,

a church that was once the target of civil rights protests for turning

away African Americans at the door.

Yet glancing at the congregation from Olivier’s vantage point shows

how limited progress has been. A sea of white faces fills the pews. It

is apparent that African-American Methodists in Jackson are celebrating

elsewhere this morning, their service undoubtedly similar, at least to

the extent that the congregation exhibits the same racial homogeneity.

“It’s like every other place in Mississippi and throughout the

country. Eleven o’ clock is still the most segregated hour,”

explains Susan Glisson, director of the William Winter Institute for Racial

Reconciliation based in Oxford. Glisson is alluding to a speech made by

Martin Luther King Jr. in which he chastises black and white Christians

for making “11 o’ clock Sunday morning,” the most segregated

hour in America.

Most religious leaders in Jackson agree that skin color can categorize

churches here. “People don’t get together to know each other.

They work together during the week, but on the weekend, they scatter,”

says Dolphus Weary, the executive director of the Jackson-based Christian

racial reconciliation group Mission Mississippi. “Sunday you get

together for the church, and Sunday you’ve got the black church,

and there’s the white church.”

Integrated Churches … Then

The racial divisions that exist between churches in Mississippi are a

byproduct of the segregated past. Up until the Civil War, slave owners

brought their slaves to church with them, although blacks had to sit in

balconies or in the basement.

“The slave master encouraged, forced blacks to go to church, but

they had to be in subservient roles. People were not allowed to become

leaders,” Weary explains. “Some of the early leaders in the

black community said that this is not right. We need to be either brought

totally into the church, or we need to start our own church.”

As a solution, many black Christians during this time requested a plot

of land and a building in which to conduct their own services, and white

ministers usually obliged. That many black and whites churches in Jackson

are related to one another in this way is a historical fact that is unknown

to many. Mount Helm Baptist Church on Church Street is a predominantly

black congregation that was established 170 years ago when whites at First

Baptist Church on State Street provided land for their slaves to erect

a separate church.

The rifts that had formed between black and white churches went largely

unquestioned until the 1960s. Then in cities across the South, many religious

leaders, both black and white, began to question the theology of segregation.

“White Southern Christians had kind of carved out a nice religious

world that had nothing to do with the world of politics, and the world

of racial suffering and conflict. We tried to isolate ourselves,”

says Dr. Charles Marsh, a professor of religious studies at the University

of Virginia. In his books “God’s Long Summer” and “The

Beloved Community,” Marsh argues that the Civil Rights movement was

invariably a religious movement.

“The Civil Rights Movement began with the Montgomery bus boycotts

50 years ago this month in Montgomery, Ala., and it was an extraordinary

year-long protest. (It) really began in pews and in churches and in mass

meetings with singing and praying and preaching. Dr. King, in fact, called

the Montgomery bus boycott a spiritual movement; he never referred to

it as a ‘Civil Rights Movement,’” Marsh says.

In Jackson, a young Methodist minister named Ed King was looking to emulate

Dr. King’s success in Montgomery. The Vicksburg native had moved

back to his home state after living in Boston for a few years. He accepted

the position of chaplain at Tougaloo College, one of the only ministerial

positions he says was available to a vocal white supporter of integration.

King was baffled by the segregation of churches, which he saw as contradictory

to the Christian command to love thy neighbor.

“What right do you have to forbid people to go to a church?”

was King’s question.

In 1963, King orchestrated “church campaigns” in which he drove

groups of black college students to pray on the steps of white churches

or barricade the doors.

“They couldn’t turn (whites) away, but what if they came with

a black person?” King asks.

However, white Protestants were determined not to worship alongside members

of the black race. Kent Moorhead, a filmmaker from Oxford, Miss., contends

that in the eyes of segregationists, churches were the “first bastion.”

“I just don’t think they wanted to worship with black people.

They wanted an apartheid religious experience, and I think that really

goes deep,” Moorhead says.

Apartheid Runs Deep

Moorhead’s film “The Most Segregated Hour” chronicles the

efforts of a predominantly white Episcopal church and a predominantly

black Baptist church to discuss their shared experiences of an event that

occurred during the Civil Rights Movement. James Meredith, a black student,

enrolled at the formerly segregated University of Mississippi. The integration

caused uproar in the sleepy town that then seeped into the local churches.

When Rev. Duncan Gray II, the pastor of the Episcopal Church, climbed

onto a statue to defend integration during the middle of a racist riot,

some parishioners chose to leave his church.

Whites trying to biblically justify the separation of races often perpetuate

the myth of Ham. According to this story, God punished Cain for slaying

Abel by banishing him to the land of Nod. Furthermore, God cursed the

progeny of Cain’s son Ham, who became the African race.

The Curse of Ham “was so profoundly ill conceived that it’s

hard to believe that it had any currency in the church,” Marsh says.

Marsh agrees with Moorhead that many whites crave an apartheid religious

experience.

“I think the idea of racial purity was one that was most pervasive

in our thoughts and lives. The ideal of the racial purity of the white

race, the virginal white woman, our faith, our home. Whites were obsessive

about cleanliness and separation, and we have ways of making businesses

ordained by God,” Marsh says.

In spite of the protection that his skin color provided, Ed King was arrested

on numerous occasions during his church campaigns. It was only after the

Civil Rights Movement had subsided that King’s efforts began to pay

off. Galloway Methodist Church, the congregation to which King belonged,

issued a statement announcing its open-door policy. Other white churches

followed suit by eventually abandoning their absolute closed-door policies.

King says that in the aftermath of the Civil Rights Movement and the church

campaigns, “all the churches I know of are integrated. Had to be

so. I think glad to be so.” More important, he says, is the fact

that “nobody would uphold segregation from a Christian viewpoint.”

Yet many leaders who deal with the greater Jackson religious community

aren’t so optimistic.

“We’ve developed a culture where you’ve got a black church,

white church, Asian church, Hispanic church. Is it racism? Absolutely,”

Weary says.

The Rev. Darryl Johnson, founder and pastor of Walk of Faith Covenant

Church in Mound Bayou, Miss., says he still deals with racism in Mississippi

churches on a daily basis. Although nationwide the denomination that Walk

of Faith belongs to is composed mainly of white congregations in the north,

Johnson says he has never experienced the type of “violent racism”

he encounters while traveling to congregations throughout the Delta.

“A few years ago,” Johnson recalls, “some young people

were telling me that they had gone to a local church in Cleveland—a

Baptist church in Cleveland—and wanted to join the church. They were

college students from a local college ... (who) desired to join the church.

The church, I understand, didn’t take them in like they usually would

take someone in. They had to have a meeting. And during the meeting, I

understand there were objections because they were black. The word did

get back to me that they didn’t accept them into the church.”

Moorhead says that many people have come to him after viewing his film

to inform him that many churches still have closed-door policies. One

viewer mentioned that First Baptist Church in Mendenhall still has a closed-door

policy, but the pastor there denies this and says that everyone is welcome

in the church. Moorhead says what’s more likely is that “officially,

that vote’s still on the books. I bet if you look at most church

histories, you’ll find that nothing’s ever been changed so that

if they were really true to their policies, they would have closed doors.”

Johnson says that “unless there has been some sort of statement that

‘we’re opening the door,’ I just assume that there still

is a closed-door policy.”

Not Black or White, But Christian

Churches in the Jackson area appear to be less plagued by the “violent

racism” Johnson witnesses in the Delta, but segregation is still

present.

For Jackson, racial reconciliation groups that worked to foster relationships

between predominantly black and predominantly white churches were a stabilizing

force in the aftermath of the Civil Rights Movement. At the forefront

of these institutions is Mission Mississippi, “a statewide movement

that encourages unity in the body of Christ across racial and denominational

lines,” as Weary describes it.

Mission Mississippi began as a series of informal prayer meetings between

a biracial group of Christians who met in a West Jackson police station.

In 1993, the group decided to form an official organization seeking to

build dialogue between black and white churches. The only event organized

for black and white Christians to meet and interact through Mission Mississippi

in its early years was a prayer breakfast held every Thursday morning.

“We would meet at a black church on one Thursday, and a white church

the next Thursday,” Weary says. “It would last for an hour,

and the first 15 minutes would be coffee, donuts, juice, or light breakfast.

There would be announcements, and the pastor would bring a five-minute

devotional. Then we’d break up into small groups of three or four

people, with a list of things for them to pray for.”

Weary signed on as president in 1998, and is well-suited to his position.

Having grown up in Simpson County during the era of segregation, Weary

was relieved to receive a basketball scholarship from a Christian college

in California. He was determined then to never return to Mississippi and

its racism. But God brought him backs, he says, “to live out my passion

for racial reconciliation.”

From 1971 to 1997, Weary served as president of Mendenhall Ministries,

a program operating out of Mendenhall Baptist Church ministering to the

needs of the poor in the area. When he arrived at the offices of Mission

Mississippi on Congress Street, the directors trusted that Weary could

take the group beyond Jackson and pitch it to other towns in Mississippi.

While the weekly prayer breakfasts continue to be a staple of the Mission

Mississippi agenda, Weary explains that he promotes partnership between

predominantly black church and a predominantly white church that results

in dialogue and community service.

“Whenever we start a chapter, we want them to do two things. One

is to meet intentionally. That is, you plan to go intentionally to a black

church, and you plan to intentionally go to a white church. That’s

putting something on the agenda that causes people to step outside their

comfort zone, but that’s what we want to do. The second we want is

to be consistent,” Weary says.

Although there are no outlines for church partnerships other than the

fact that they extend across racial divides, Weary encourages the partnership

of churches that may have shared experiences of the segregated past. Mount

Helm Baptist Church and First Baptist Church are a natural match, for

example, because Mount Helm was started by the slaves of First Baptist

whites. The prospects for that partnership are looking good. When Mount

Helm celebrated its 170th anniversary in October, members of First Baptist

showed up at the celebration.

“We had (the churches) at the prayer breakfast together,” Weary

says. “We introduced those pastors together and were saying, ‘Guys,

it would be a really great model if you guys start thinking about a partnership

together.’”

A Matter of Style

It may, however, seem that Mission Mississippi is selling integration

short if it does nothing to bring whites and blacks together under one

roof every Sunday.

Like most of those working on racial unity, Weary recognizes that blacks

and whites have different styles of worship. These differences are rooted

in the segregated past. Because black ministers didn’t attend seminary,

their services were more improvisational, later becoming infused with

the verve of gospel music, whereas extensive religious education led white

ministers to be more formal.

Moorhead is blunter about the difference in worship styles. “Black

churches are fun to go to, and white churches generally aren’t,”

he deadpans.

Sacrificing these cultural identities would contradict the spirit of integration.

What Weary promotes instead is “churches that are racially different

and that periodically those churches are coming together.”

Weary commends New Horizons Church and Trinity Presbyterian Church for

being outstanding examples of partnership churches. “They have intentionally

been working on coming together for the past 11 or 12 years, and they

have done a number of things together to the point that people in the

congregations are doing things outside of church,” he says.

The alliance between New Horizons Church and Trinity Presbyterian Church

actually predates the formation of Mission Mississippi by one year. On

Easter 1992, the two churches joined together at Belhaven College for

a sunrise service. The Rev. Michael Ross moved here that summer to become

the new pastor at Trinity Presbyterian, and he was quickly approached

to take the relationship with New Horizons a step further by entering

into a “sister church relationship.” Ross worked closely with

Pastor Ron Crudup at New Horizons to bring their churches together.

“We had the Lord’s Supper at our church, and the Lord’s

Supper at their church the next year,” Ross says. “And that’s

a big event: for whites and blacks to celebrate the Lord’s Supper

together.”

Trinity Presbyterian was a progressive white church from the beginning.

Founded in the 1950s as a church for GIs, Ross says that Trinity “was

basically untouched” by the evils of the Jim Crow era. “That

seemed to happen in larger churches like Broadmoor and Woodland Hills

and First Baptist. Places like that,” Ross says. “They had a

pastor here named Park Moore, and he was very much in favor of civil rights.

He said if people could come to the church, they’re free to come.

Part of them agreed with him, and part of them didn’t, but they didn’t

fire him or anything.”

When Ross arrived in 1992, he brought some African Americans who lived

in surrounding neighborhoods into the church. What resulted was a fairly

racially diverse congregation. Yet Trinity still had a lot to learn from

the relationship with New Horizons Church, the church founded by Crudup

in 1989 that featured only a few white members. “I don’t know

if there were any preconceptions,” Ross says, “but we went about

it slowly.”

After mission trips to Africa, prayer meetings, and continuing the sunrise

service on Easter Sunday, Ross says his congregation has learned that

“to work together doesn’t necessarily mean you have to worship

at the same church.” Meanwhile, Crudup says the greatest thing his

parish has learned is that “people of other races are just people.”

In spite of being the catalyst for some change in the way that black and

white churches view one another, critiques of Mission Mississippi abound.

At its outset, Mission Mississippi decided to restrict its efforts to

Christian churches. This came at the expense of including other faiths

with an interest in building relationships with members of a different

race. Weary explains that his organization is not “against the Jews,

we’re not against the Muslims, we’re not against anybody. We’re

pro, if we can get this group of people who say they have so much in common

(through Christianity), then how much better our whole state will be.”

‘Wasn’t None of Them White’

“There is little progression within the Mission Mississippi movement.

It’s driven more by businessmen, and in Jackson, it’s driven

by successful businessmen. You’ve got some churches that help support

it a little bit. One of the big pastors would come speak to give some

assent to it. They would have Dolphus come speak on a Sunday night or

something. But (nothing) as far as them being really involved and saying

racism is wrong,” John Perkins says.

Perkins is perhaps the most important figure in racial reconciliation

efforts in Mississippi. He is a mentor to Weary, who grew up under him

at Mendenhall Ministries, an organization which Perkins established. Both

men have much in common. Perkins grew up in New Hebron, Miss., and moved

to California where he witnessed “good experiences across racial

divides.” Perkins did decide to return to Mississippi, though, and

established several foundations addressing poverty and racial relationships.

Perkins is critical even of his own racial reconciliation group, The John

Perkins Foundation, saying it has done “very little” to mend

racial relations. Perkins doesn’t blame either organization; rather,

he believes that it is the fault of most white and black churches for

not rising to the challenge. This, he says, is due to the inability of

blacks and whites to trust one another in order to enter into a working

relationship.

“Blacks now have gotten trapped because they don’t trust the

white church to do what they need to do, and they’ve become locked

in their black church. So the church as an institution is still very segregated,

because the white church took a long time before they invited a few blacks

to come in,” Perkins says.

This is echoed by Moorhead, who portrays in his film the stagnation and

misunderstanding brought about by failing to ignite dialogue between the

black and white communities. After 30 years, St. Peter’s Episcopal

Church and Second Missionary Baptist in Oxford decided to come together

discuss their shared but different experiences of the racist past. This

came after St. Peter’s priest, Duncan Gray III called Rev. Leroy

Wadlington at Second Missionary.

“Leroy,” Gray said, “I’ve just come out of a meeting

and a question came up. What was feeling of the black community when all

of that was going on.”

Moorhead’s commentary is that no one could answer, because everyone

was white and didn’t know who to ask.

As congregants from both churches met to engage in discussion, ingrained

notions that each race possessed of the other began to spill out and illuminate

the reasons why an attempt at racial reconciliation hadn’t yet been

made. Whites mentioned feeling guilt, but defended themselves by saying

that they just “hadn’t gotten around to” addressing the

obvious separation of cultures. African Americans conveyed a sense of

disempowerment that left them feeling unable to approach white people

to begin the reconciliation process.

“Black people don’t feel automatically invited, they automatically

feel the opposite. From a white perspective, you have to work to break

down that barrier and overcome the suspicion because the suspicions are

based on long experience,” Moorhead says.

It is evident from the film that economic discrepancies also play a complex

role in the hindering status of reconciliation between the races. At the

beginning of the film, an African American teenager explains her inability

to understand the white race because she “grew up in the projects.

And wasn’t none of them white.”

Perkins argues that the fact that poverty is a result of past white domination,

and also argues that poverty continues to leave blacks feeling disempowered,

which makes true reconciliation impossible because true reconciliation

implies equality. Perkins’ solution is that when churches join together,

such as through Mission Mississippi, the activities they perform to achieve

racial reconciliation should be service work in the community. Worshipping

together is not the end, he stresses. “Working together will bring

us closer together,” he says, and “go a long way in eliminating

poverty.”

Other groups in Mississippi are working to achieve reconciliation by reopening

old civil rights cases in which justice was never served. Last year, the

William Winter Institute was called upon to facilitate a series of meetings

at the First Methodist Church in Philadelphia to decide how to celebrate

the 40th anniversary of the murders of civil rights workers Schwerner,

Goodman and Chaney. Although the William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation

is not faith-based, director Glisson says that the institute has worked

with churches in almost every community it has served.

At the Philadelphia coalition, Glisson says the institute “acted

as a facilitator, helped people to tell their story, helped them work

through what they believed could bring about redemption in the case.”

The group that met was comprised of thirty multiracial citizens. Inevitably,

disagreements that hinged on different perceptions arose. “African

Americans who were at the table said the way they would like to commemorate

the 40th anniversary of the murders was to have a march. And the white

folks sort of got more pale than already are because for them, marches

signify riots and protest,” Glisson says.

After five months of deliberation, the group agreed to issue the Call

for Justice, a petition calling for the reopening of the case of the murders

of the Freedom Summer workers, at the county coliseum. It was at this

point that another group, the Mississippi Religious Leadership Conference,

decided to step in and help. The MRLC had grown out of the Committee for

Concern, the group of religious leaders who had met to remedy the burning

of black churches during the Civil Rights movement.

“We’ve been now for 41 years an organization that sought to

work for the betterment of people that perhaps didn’t have a voice

themselves,” says the director since 2000, Dr. Paul Jones.

During the deliberations, Jones received a phone call from a member of

the Philadelphia Coalition asking if the group would be willing to start

an award fund to reward any new information in the Mississippi Burning

trial. Jones agreed, and negotiated a contract with donors who placed

an excess of $100,000 in the fund.

Efforts of each organization paid off: In June 2005, Edgar Ray Killen

was convicted for the murders of the Schwerner, Goodman, and Chaney. “I

think they’ve taken a big step in holding one of the murders accountable,”

Glisson says.

But there are still cases in which justice has yet to be achieved. In

July, Thomas Moore approached Dr. Jones about starting a reward fund of

his own. Forty-one years earlier, Moore’s brother Charles Moore and

friend Henry Dee had been picked up by members of the Klan while hitchhiking

and murdered. When Moore revisited the scene of the murder with a Canadian

filmmaker and the Jackson Free Press in July 2005, Moore discovered that

one of the killers who was reputed to be dead was, in fact, alive.

Moore recalls hearing a Klansmen recount a portion of the eulogy of James

Ford Seale. “I can’t remember how they said it, but he had a

good life. They raised three kids and lived and had a good job and retirement.

The Lord had been good to him. I said, ‘Now wait a minute. If we

serving the same God and the same Bible and the same beliefs, I believe

the Lord said, ‘Thou shall not kill…’ If God blesses that,

and we believe in the same God, then the God I’m serving is not true.”

Jones worked with Moore to establish another fund for information leading

to the murders of Charles Moore and Henry Dee. The reopened case is still

in the investigative stage. But if nothing else, working with Jones, a

white Baptist minister, has helped Moore with reconciliation of his own.

“I didn’t really think about it when I met Dr. Jones, but as

I worked with him and began to realize, hey, this is something big. This

something mighty fine,” Moore recalls.

“Forty-one years ago, (Charles Moore and Henry Dee) were killed by

the KKK, which is a predominantly white organization as far as I know.

Now another predominantly white organization is trying to reach in and

help. That is a tremendous breakthrough.”

© 2005 The Jackson Free Press

|